Today, let’s talk about trust.

One of the things that goes on in large organizations (yes, I’m building up to something) is these Systems. You know. Systems for Planning, Approval, Control And Reimbursement for Travel, Creation of Vendors, Buying Doughnuts, Going To Vacations, Politely Scratching Your Arse. You know. Yes, of course, when you have 3000 people operating in a complex legal environment, it makes sense to have a piece of software to track their vacation days. Of course it makes sense to have a place where these folks collectively clocking millions of air miles have a place to file their expenses. Sure. But this does not explain the sheer monstrosity and rigidity these Systems tend to develop to. Their sole purpose in the end seems to make the life harder for their users, not easier. How come?

One of strong reasons for this is trust.

Let’s take an example. At a hypothetical organization, there is a simple travel policy. When somebody needs to travel, they drop an e-mail to the travel assistant and cc their direct boss. The former organizes hotels, tickets and what not and the latter approves (denial is a huge exception) the trip. Simple, straightforward and flexible: everybody sees that a guy approaching 7 feet would need to fly business to US west coast and that you should stick around for at least a week while you are there. As the company grows, the system grows as well as two assistants can handle a sizable amount of travel requests and people don’t fly that often. Inevitably, however, there will be this one guy who discovers the pleasures of flying business and the sweet life of California. So he goes there often. Like on a monthly basis. From Europe. Whether he actually needs to or not is besides the point. The point is that the travel budget inevitably goes “clonk” and the person responsible for it goes “Yikes!”. As going “Yikes!” is an unpleasant experience and, after all, she is responsible for the budget. So a rule is established that business travel is only permissible for people at a certain pay grade and/or for durations of x hours and/or specifically approved by the boss.

These rules being in place, people go “Oh, these are the rules? I did not know it was actually OK to fly business!”. And they do because convincing your nice boss is not difficult. You know, there will be a meeting the day I land and I need to look the part. And I am a manager after all, it is allowed to fly business!

This, of course, leads to more budget being spent and more rules put in place. Which in turn leads to people discovering inventive ways to get around the restrictions. For example, it turns out, that if you wait until the very last minute to book your trip, often business class seats are all that are there and you absolutely need to make that meeting, don’t you?

In the end, the list of rules become too complex to follow by any single person and software is put in place. A System. In a short while, the travel costs soar, people swear and curse as it is impossible to plan travel the way they need to and somebody gets paid handsomely to maintain the entire machine.

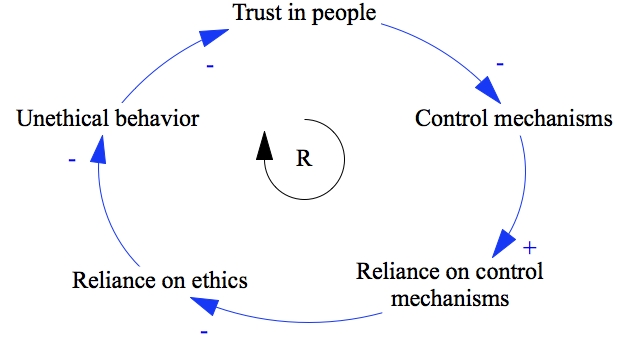

For the general case, the cycle looks like so:

Decline in trust in people leads to increase in control mechanisms (this is indicated by the “-” sign) which in turn lead to reliance in control mechanisms (“I’m good as long as I’m within the rules…”) which decreases reliance on simple ethics (“… regardless of whether it feels right or not”). The latter, of course, leads to increase unethical behavior that drives down trust in people.

In the end, a huge amount of trust is destroyed and good honest people are taught to weasel and scam. I don’t need to tell you what this does to the intellectual capital of the organization. In the organizational culture framework developed by Desmond Graves and Roger Harrison, this also means the organization drifts towards more centralization and more formalization. Regardless of whether this is a culture that supports the current strategy or not. Which is not good.

What can be done, then? Resist. The fact that somebody has a different understanding of the common value set should not mean that everybody needs to suffer. Just give the offending person a good round of managerial spanking to pull them back in line. Also, it helps to remind people of the shared values. Upon every opportunity. Really. Often. But not too often. The point is that it needs to be absolutely not OK for people to waste company resources. It must be an offense that leads to people not talking to you. Or talking to you about that it is not OK to do stuff you did. Loss of respect. That sort of thing. Simple managerial skill and talking to people goes a long way!

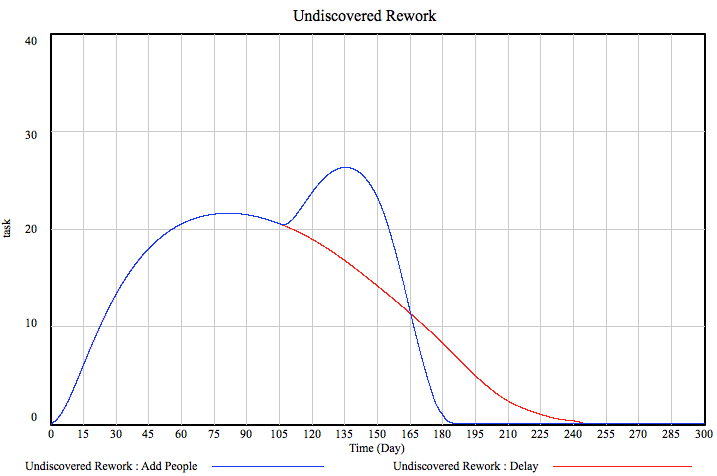

Hope this got you thinking about what goes on in your organization. Have a good weekend and enjoy System Dynamics in action!