So this is it. After years of hard work, there is finally some success to speak of. That’s a good thing, right? Well, yes. And no.

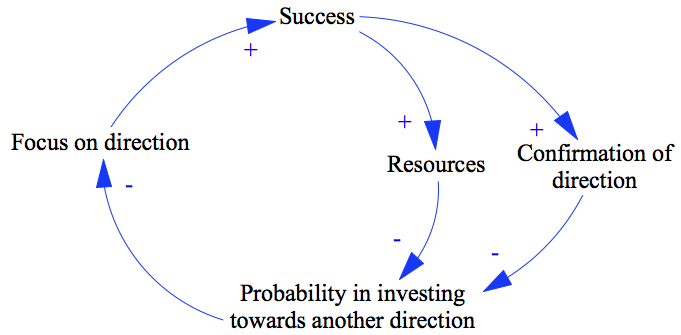

Let me elaborate. When you are successful, two things happen. The first is money. The more successful you are the more money there is. Actually, to be more generic, you get more “resources”. For an artist this might mean more freedom to do whatever they want, for a scientist this might mean recognition from peers and for a businessman this usually means money. The second thing that will happen that, all of a sudden, you are sure of your direction. Or more sure in any case. A startup is just a bunch of people with a crazy idea until the idea actually attracts users in the real marketplace. There is no way to be sure an idea will work until it has, well, actually worked.

You’ve got money, you’ve got a confirmation that your initial idea was good, what do you do? Let me tell you, based on personal experience, very few people go “Right, that’s that, then. I did this thing and it was good but now I’m going to take a risk by doing something completely different”. People will retire, oh yes, but majority of organizations and individuals tend to invest into the idea that brought them success. It makes sense, right? You’ve found a goose that lays golden eggs. Take the money from some of them eggs, hire a bunch of guys and go catch a herd of the suckers! You’ve got the recipe of a dish everybody likes, of course you are going to use their cheering as motivation to cook it again!

A well-funded and well-motivated individual focusing on doing something great they have already succeeded at once? Even if they were just lucky the first time around, chances of failure are slim under the circumstances. More success is unavoidable.

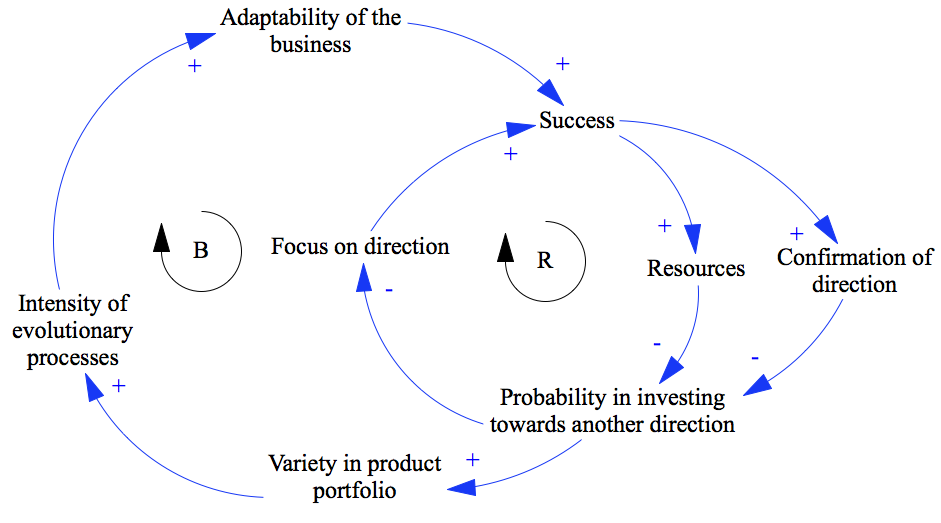

The entire model looks like so:

Success leads to money and confirmation which in turn drive down the likelihood of deviating from the set course which brings about focus and more success.

Brilliant, right? Kodak did this for 70+ years. Microsoft has been on this cycle for ages. IBM. GE.

No, not really. What this means is that the flexibility of an organization goes down. In the beginning, yes, its just the desire to choose a different path that goes away but soon the ability gets removed as well. After posting record profits for 10 consecutive quarters, your shareholders will not look kindly upon a CEO that proposes a radical change in direction. At some point an organization becomes so committed and invested in that one direction, even deliberation of change becomes hard. When everyone around is a chemist (or a software engineer, for that matter), who is there to experiment with hardware? Amazingly, Kodak actually managed to launch a digital imaging product as early as 1991 but the spectacular lack of success in the later years confirms the conclusion. The more successful you are the less likely you are to consider a change of direction.

Loss of flexibility is not a bad thing. Just like flying is not a bad thing. Its the hitting the earth part that gets you. When markets change and you don’t, things are not looking up.

Then there is the loss of variety.

Let’s think of Darwin, for a moment. He stipulated survival of the fittest. But what if everyone is equally fit? If you have a herd of mice, only the ones most successful in the given environment will survive and produce offspring. Should the conditions change, the definition of success changes, a different set of traits becomes desirable and the population survives. Given a bunch of genetically identical mice, however (let’s assume no random mutations), all the mice and their offspring are equal. If the environment is favorable, they’ll proliferate. But when the conditions change, they are doomed as there is no alternative set of traits to take over. There is none fitter to survive. The same goes with companies:

Single-mindedness in direction drives down variety in product portfolio (the “+”, as always, does not denote a positive influence but the fact that the variables move in the same direction). That reduces the intensity of evolutionary processes (our mice become more similar). This in turn reduces adaptability and eventually reduces chances of success.

What can we learn from this? Firstly, I think, it is not realistic to expect companies not to follow the cycle described earlier. People are not built that way. They will inevitably continue doing more of what makes them successful. Secondly, it seems that balancing the two cycles each other is a viable option. If the balancing loop kicks in when the success has already worn thin because of management failures or market issues, the company is done for. But if you manage to make sure both loops happen more or less simultaneously, survival is possible. Think of IBM. It was hit hard by changes in how computers are made but still had enough resources left to kick the cycle going backwards (lack of success reduces confirmation of direction which diversifies the portfolio) and to re-invent themselves. Few enough companies have pulled this off to call it a miracle of management.

Sidenote: there is interesting research on the topic of business survival. It seems that the pace of change is accelerating and companies die faster as they are no longer capable of adaptability the environment assumes. There is a good book about the topic as well.

Will your company be the next IBM or Kodak? Think about it while you enjoy System Dynamics in action!