Since the previous post got a lot of good feedback and a ton of comments. Let’s follow up.

The question is, why is G+ flopping? I mean, its like a desert, Steve Yegge’s rant is the only piece of content I’ve ever found there. And even that was referred to from somewhere else.

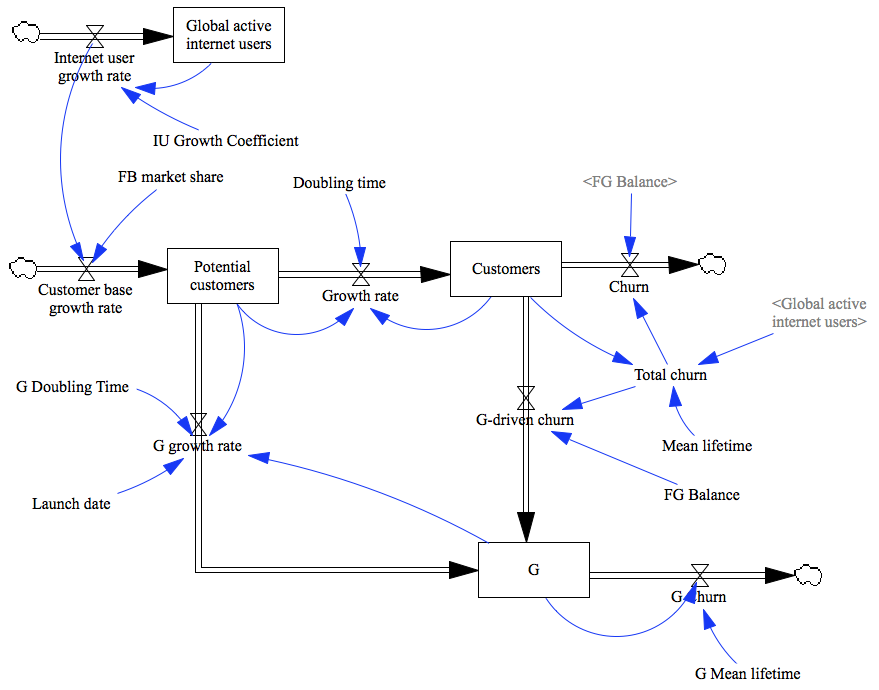

In a wider context the question is, what would it take for something brand new to take on Facebook and significantly alter the behavior depicted previously. To answer this, I amended the model:

As you can see, it is now considerably more complex. There is now a new box ingeniously labelled “G” and a flow from potential users that fills it. By doing this, an assumption is introduced that the potential customers of Facebook and the new service will overalp. There is also a flow from “Customers” to “G” and considerable changes in how churn is calculated. Previously, as you might remember, churn was just a function of how many users Facebook has and depended on the average lifetime of active users (whatever the definition of an “active user” is). This is slightly unrealistic: the less users facebook has, the less reason for people to be there as the chances of majority of their friends not being active goes up. So I fixed that. Total churn is now calculated like so:

Customers/(Mean lifetime*(Customers/(Global active internet users))^0.07)

The “0.07” effectively determines how fast the function approaches 1, i.e. how much impact the outside world has on churn. A new variable “FG Balance” determines, what percentage of the people leaving Facebook would become active users of the new service.

Let’s now take a look at how these changes affect what we can say about the future of Facebook. Let’s start simple and just assume that the new service is after the same user base but that the existing Facebook users are extremely loyal and there is no leakage, this shall be our scenario “G”. The G doubling time parameters are set to match what is known of G user base, mean life-time is the same as for FB and the service is set to launch on day 2692 of Facebook Reckoning with 2.5e+07 users. The reason for this is that the behavior of the networks is very different in the beginning and at scale simply because their target community changes so much. Remember how Facebook conquered one small college market after another (why this matters, is a small thinking exercise for you, my dear reader)? Remember the rush to get early G invites? Anyway, here we go:

Yup, there is no way the new service will catch up with Facebook like this. Even when we make the new service virtually explode by making it grow three times as fast as the figures suggest (scenario “Super_G”), it will not overtake Facebook before 2015. The reason for this is simple: scale is king here. The more users you have, the more you attract. Thus, tapping potential customers is not enough, G needs to attract FB users. Let’s see what happens if a third of people leaving FB would join G:

Oh my. Even for that rather generous case, the blue line crosses the red one in about five years… In both cases, it is interesting to note te effect on Facebook: for both scenario its fundamental growth pattern does not change. It will flatline a while longer or loose some customers for a while but it will eventually continue to grow and grow fast.

This is not looking very promising, is it? Let’s dial everything to pretty much eleven and picture a scenario where two thirds of all people leaving FB would join G and that the competing service is so attractive that the average half-life of FB users drops 30% (Scenario “G_Super_Pull”):

This is much more interesting. FB general behavior does not change but G growth takes a sharp turn up as soon as FB churn peaks. Which is right about now, more or less. Ergo, a similar scenario might be happening and we don’t know it yet. That said, the input parameters are pretty outrageous and very unlikely to be true and the FB should have less users now already. Still, it is curious to think that G might be about to overtake Facebook and nobody knows it yet. Interestingly, changing the percentage of Facebook churns converting to G has less of an impact than the overall increased churn of Facebook.

Interestingly, the fundamental modus operandi of Facebook will not change: some scenario prolong the flatline phase and some induce a small decline but all the lines point up. Playing with the “effect of the outer world” constant has little impact as well.

The main conclusion I can draw from this exercise is that Google needs to actively target Facebook users, convert active facebookers who are happy with the service to active G+ users to have even a remote chance of making a dent in their armor. Rapid user acquisition would not do, only conversion. And the conversion rates must be very high indeed.

The second, and more important conclusion seems to be that one needs to mess up royally to loose in the social network game. The amount of people joining the interweb is so large that even with massive churn and people quitting in favor of your competitors, there is still a huge crowd of people to recruit. Which is something I would not have thought.

As we are done now with the analysis part, it is probably appropriate to point out that this model has an important flaw. It assumes that Facebook and Google define active users similarly. This is unlikely to be true: Google calls even their reader app part of G+ so God knows what their numbers might actually mean. It was also pointed out that there is actually little churn in social networks, you just don’t stop by as often as you used to but you never churn. And there is the question, how can we use such insights to predict future growth.

But, yet again, the ink in my pen has dried and the answers need to wait until next time. See you around!